From

$10,000 to $125 million:

Why

compound interest is the 8th wonder of the world

I can show you how to turn 10 grand into a private-jet-level fortune!

The only problem? It takes 92 years. So your fortunate grandchildren are the ones who will actually end up with nine-digit wealth.

But you can harness the same incredible power to work for you, within your lifetime! No B.S., no tricks.

Stick with me, and I’ll show you how it’s done.

***

Recently, I’ve gotten my hands on data for various types of investments. The best dataset I’ve found stretches from 1970 to 2019, in the form of a couple different ‘fine-tuning’ tables on the website of personal finance expert Paul Merriman and his colleagues Daryl Bahls and Chris Pedersen.

I keyed their data into a spreadsheet, so I could play around with it myself.

Playing around with numbers on a spreadsheet is just barrels of fun, right?

Believe it or not, it can be! It sure was once I started examining what happens to money in various investment scenarios. And once I saw some of the outcomes, my jaw literally dropped open!

Not ‘literally’ as in figuratively, for emphasis. My mouth really did fall open.

And the best part is that this isn’t some theoretical exercise. This is based on what actually happened. This is history!

I’ve got some data stretching from 1928 through the 92 years ending December 31, 2019. For convenience’s sake, I started with a lump sum, and calculated what would have happened over that long span of time if you put $10,000 into different kinds of investments.

For example, from 1928 to the end of 2019, the S&P 500 would have turned $10,000 into $60,351,749. Not a typo. That’s over $60.3 million dollars!

Not bad!

Okay, I can hear the complainypants already: But the S&P 500 wasn’t around in 1928. You couldn’t actually do that!

That’s true. But researchers from academia and from financial companies have determined a rough approximation of which stocks would have comprised the S&P 500 back then.

Low-cost mutual funds didn’t exist yet either, at least not for individual investors like you and me.

So this wouldn’t have been nearly as easy as it is today. But it’s based on what really happened in the markets. While it’s certainly not exact, the data is close enough for our purposes. Mutual funds do exist today, and that’s what’s most important as we venture into the future.

So no more griping. Just sit back and appreciate the incredible wealth-building power of compound interest over time!

Over the same period of 1928 to 2019, a large-cap value fund would have done even better than the S&P 500: it turned $10k into $166,664,554.

That’s right. From $10,000 to $166 million.

So, you might be wondering at this point, what’s the absolute best-performing asset class since 1928?

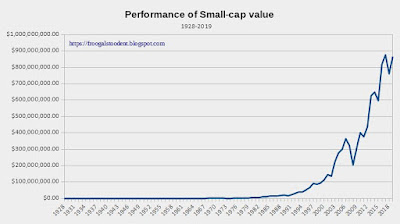

The answer is: a small-cap value index fund.

$10,000 invested in a small-cap value fund in 1928—just at the peak of the Roaring Twenties, and less than two years before the start of the Great Depression—would have turned into an astonishing $865,767,371 by the end of 2019.

I’ll stop for a second so you can pick your jaw up off the floor.

$865 million. That’s eight hundred sixty-five million dollars. Nine digits.

If you want to get technical, it’s actually closer to $866 million. But hey, what’s a million between friends?...

Believe it or not, this is the same graph as the top of the page; this one has a standard scale while that one is a logarithmic scale. Comparing the two, you can see the disadvantage of the standard scale shown here: the performance looks flat for about 60 years. But the log scale shows that it’s anything but!

What About Real Estate?

Think about this for a second. In 1928, a typical house cost about $8000.

So if your grandparents had an extra $10 grand, they could have bought a pretty nice house with that money. Suppose they passed that property down through the family over the years. If your family took good care of that property, let’s say it might be worth $400,000 today.

If your family rented the property out for that entire time, the total sum of the rent collected over the course of 92 years would probably fall short of $1 million.

So the house would be worth in the neighborhood of $1.4 million to your family. Minus the costs of maintenance, repair, and insurance. And property taxes.

If, instead, grandma and grandpa had opted to invest in a broad variety of relatively small, out-of-favor, publicly traded companies, your family could instead have over three-quarters of a billion dollars today!

And stocks don’t require plumbers or 30-year roofs.

Still think real estate is such a great investment?

Investing For The Long Haul

So where’d I get the $125 million mentioned in the title?

As a matter of fact, it comes from an initial lump-sum investment of $10,000 in 1928. Of that amount, 80% went into an index fund that tracks the S&P 500, and the remaining 20% went to a small-cap value index fund.

The ending balance of this portfolio, at the end of 2019, would be $126,153,636.

But such huge numbers can give you bleary eyes. Numbers like $126 million, or $865 million, are totally out of reach for the disappearing middle class like us, right?

Instead of dealing with titanic sums of money, let’s focus instead on a timeframe that we can actually wrap our heads around.

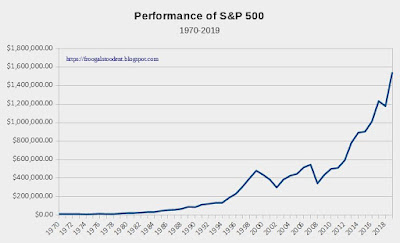

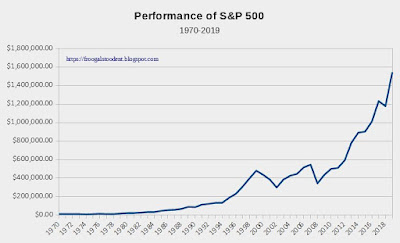

Suppose for a moment that the returns for the next 50 years exactly mirror the returns from 1970 through 2019.

They won’t, of course, but just play along with me for a second.

From the opening of the market in January 1970 through December 31, 2019, the S&P 500 compounded at 10.6% per year, on average.

That doesn’t mean it went up by 10% every year. Oh, no. It dropped by as much as -37% in 2008. And the biggest yearly gain was almost +38.5% in 1975—which came right on the heels of two straight years of punishing double-digit percentage losses.

The ride was definitely wild. But there were more up years than down years.

And over the long run, it averages out to +10.6% per year.

A $10,000 lump sum invested in the beginning of January 1970 would be worth over $1.5 million by 2019, as Paul Merriman and I observed in our recent interview. So, supposing that returns for the next 50 years end up going exactly like 1970 to 2019, that means that $10,000 invested today would end up being worth about $1,544,000 on December 31, 2070.

Assuming inflation also follows the historical pattern, that’ll probably be enough for you to retire on. All you have to do is put $10,000 into an S&P 500 index fund, once, and forget about it for 50 years.

Boring Name, Exciting Results

But unless you’re under 25 years old, there’s a good chance that you won’t actually have 50 years of compounding to multiply your money.

Fortunately, there’s a shortcut. It’s well-known, and every personal finance writer and blogger talks about it. It’s called dollar-cost averaging.

But that sounds boring, and very few people show you exactly how powerful and exciting this shortcut can be!

Well…guess I’ll fix that.

I’ve prepared a downloadable spreadsheet for this little demonstration. I left the formulas in the cells, so you can see my work.

I used LibreOffice Calc, one of my favorite free and open programs, to create this spreadsheet. If you really want to play around for yourself and change some assumptions, you can download LibreOffice. Microsoft Office or Google Docs should work well too.

We’ll open the demonstration with the S&P 500 first, using the 1970-2019 dataset. Then we’ll get into an even better portfolio option.

OK. Ready? Our demonstration begins:

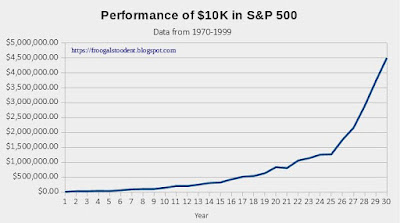

Let’s suppose you’re 25 years old. You decide to invest $10,000 a year, every year, for 12 years. You’re investing in your 401(k), so the money’s coming right out of your paycheck. You never even miss it.

Out of the various options in your 401(k), you’ve selected a low-cost S&P 500 index fund. A solid choice!

After 12 years have passed, life happens. Your house needs some work, the growing kids are requiring more money now, and so on. You decide you can’t continue to contribute to your 401(k), and you never add another penny.

Over 12 years, you’ve put in a total of $120,000 of your own money. Now, you just let it ride in that S&P 500 index fund—you don’t take any money out, you don’t put any in.

Remember, we’re assuming the market performs exactly as it did from 1970 onward.

So after 20 years have elapsed, how much is that fund worth?

A: $838,227.

You put in $120,000 over 12 years. After just eight additional years, your total is over $800,000! How does that work?

That’s the magic of compound interest, baby!

Simply put, you’ve bought a tiny ownership stake in about 500 companies. As a shareholder, you are therefore entitled to a share of their profits, which is paid out in the form of dividends. As long as the companies continue to make money, people will be willing to pay for a share of stock.

As history shows, the actual value will fluctuate on a daily basis. Sometimes by a lot. But you’re not trying to buy today and sell tomorrow for a profit. That’s day trading, and it’s awfully close to gambling.

You’re not a gambler. You’re a long-term, buy-and-hold investor, just like the academic research says you should be. This week’s market returns only matter if you’re planning to retire next week.

But in the current example, you’re only 20 years into your career, at age 45. Let’s keep going, shall we?

5 years later, you check in again. You’re now age 50. How much is your fund worth?

$1,271,649.

Whoa. When did you become a millionaire?!

You think to yourself, “I’ll let it go for another 5 years. And then if it’s still doing well, I’ll consider retiring early!”

Alright, fast-forward. It’s been 30 years; you’re now in your mid-fifties.

Five years ago you discovered, to your great surprise, that you were a millionaire! But since then, you’ve heard the news, and you’ve heard people talking at work. Your friends have commented on how “the market” has done lately. People have remarked how it’s gone down. And then they say it went way up. Then it’s down again. Lately, people have been saying it’s up again. You have no idea what to expect.

Can you afford to retire now? Let’s see the results.

As it turns out, the last 5 years have been a raging bull market. Though it may have dropped for a day here, or a week there, it’s mostly been up, up, and away. And at the end of year 30, your $120,000 investment is now worth…drumroll, please…$4,501,114!

Think you can retire on that?

Heck, with that kind of money, you could roll it over into a total market bond fund and live off the dividends alone!

Since 2007, total market bond funds have typically yielded about 2% to 2.5% in dividend payments (it has been over 4% in a couple years during that time, but we’ll be cautious and estimate low). That’s not counting the price movement of the fund itself; we’re only counting dividends.

So you could roll that $4.5 million over into a total market bond fund, and figure on yields of 2% per year—that’s $90,000 per year in interest. And you still get to keep the $4.5 million, which will continue to throw off $90K or more every single year!

And remember, we’re estimating conservatively at 2%. Some years, you could easily get double that rate—that’s $180,000 a year to live on!

But, you think, some of these stocks pay dividends. As far as I’m concerned, that’s basically the same thing. Instead of selling the stocks and buying bonds, why wouldn’t I just leave the money in stocks and live off the stock dividends instead?

You could.

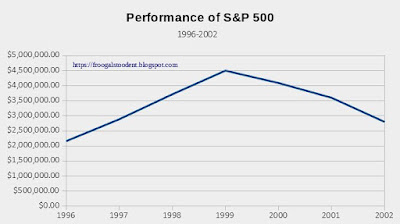

But here’s why it’s not a good idea: it turns out that the market proceeded to drop, for three years in a row.

So you’ve retired at age 55, with $4.5 million. And, since you left your money in stocks rather than converting some over to bonds, at the end of year 33, your S&P 500 fund is now worth $2,799,021.

Still a lot of money, but going from $4.5 million down to $2.8 million is enough to test even the strongest stomach. Especially if you’re a new retiree.

You’ve been planning to fly high on your dividends. But, since the market has taken a beating, you might have to start withdrawing the principal. Meaning that your $2.8 million is about to take yet another hit because you have to buy food. And pay property taxes. And pay for electric and other utilities. And insurance. And heaven forbid your furnace stops working this winter…

See why people are scared of the stock market?

But you shouldn’t be; you just have to keep it in perspective. Over 30 years, stocks have made you wealthy enough to retire early, and live comfortably off that money!

However, you’d be wise to get more defensive if you’re going to retire soon. And this example, based on historical data, illustrates why.

Don’t be scared of stocks. Over the long term, they are far and away the most likely asset class to make you wealthy. It’s just not wise to rely on them for income during retirement.

That doesn’t necessarily mean that you should have zero dollars in stocks during retirement. It’s just unwise to have 100% of your money in stocks. Or 90%. Or even 80%.

A Better Option

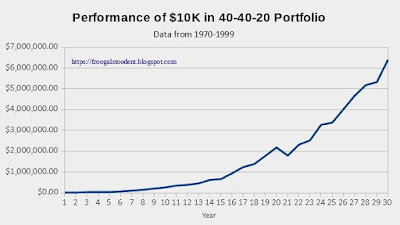

But I promised to get you into a better portfolio than the S&P 500 index fund. So let’s proceed, with the same lifestyle assumptions and the same historical performance data.

Instead of getting only 500 large companies, you’ve listened to Paul Merriman and the Froogal Stoodent about the importance of massive diversification. You put 40% of your money into a total US stock market index fund like VTSAX, another 40% into a total world stock market index fund such as VTIAX, and the remaining 20% in a small-cap value fund like Vanguard’s VBR, or Fidelity’s FISVX.

VTSAX gives you around 3500 U.S. stocks, and VTIAX holds over 7000 non-U.S. stocks.

Remember earlier, when I said small-cap value is the asset class with the highest returns? In this example portfolio, I allocate 20% to that small-cap value index fund. You could make that a higher percentage, but remember that such high returns also come with dizzying ups and downs.

Most people get extremely nervous when they see those massive drops. If you’re comfortable with watching your investments get pummeled, year after year, you could put 50% or more in small-cap value.

But we’re emotional creatures, and you’re unlikely to stay the course when everybody’s screaming about how their retirement money’s going down the drain. You’ll start to worry about yours, too. It’s human nature.

You should stay the course anyway; you won’t need that money for years and history shows that the market will recover.

But that’s simply not how we think. So it’s best to develop an allocation you can live with, even during the bad times.

Therefore: 40% total US market, 40% total world market, 20% small-cap for an extra shot of growth.

Cool?

Okay, let’s proceed, just like before. Twelve years, 10 grand a year, total of $120,000 invested.

So, at the end of year 20, what is this portfolio worth?

$2,186,454.

Yeah—even more diversification than the S&P 500, and nearly three times as much money! Isn’t playing with spreadsheets fun?!?!

And how much are we talking about after 25 years have passed, when you’re age 50?

$3,380,019.

How about at the 30-year mark?

$6,401,727.

-In case you’re curious, after 35 years in this exercise, you end up with $11,500,273. And after 40 years, you’re aged 65, with a whopping $13,503,640. Note that you turn 65 just one year after the largest crash of the entire 50-year dataset. (Yep, you guessed it. I’m talking about 2009, just one year after the Great Market Crash of 2008.)-

Assume you’ve chosen to retire at 55, with $6.4 million. You roll that money over to a bond fund, and simple math shows that your dividend income of 2% per year amounts to $128,000 per year.

That’s more money each year than the sum of your contributions!!!

Boom! Dollar-cost averaging and compound interest. What else do you need?

How To Start

To start investing so this process can work for you, here’s what you have to do:

Step 1: Decide on your asset allocation. Everybody’s got different ideas; I have a few of my own. The Two Funds for Life portfolio recommended by Paul Merriman, Richard Buck, and Chris Pedersen is a good choice for most people. But basically, stocks are for growth and bonds are for stability. Arrange your allocation accordingly, and be sure to use low-cost index funds.

Step 2: Set up your account.

Your first choice is probably a 401(k), though it may be a 403(b) or TSP or other type of retirement plan (called a ‘defined-contribution’ plan by those in the biz).

Whatever the case may be, arrange with your employer to contribute money out of each paycheck. They’ll often ask you to specify a percentage, like 1% or 4% or 7.5%. Your employer’s plan provider (perhaps Schwab, Edward Jones, Fidelity, Voya, or Vanguard) may have a webpage where you can set everything for yourself.

If your employer doesn’t have a plan like this—some don’t—you could always set up a brokerage, which is self-directed. A brokerage does not have tax advantages, though you could open a traditional IRA (or a Roth IRA if you prefer) through your brokerage house.

The main advantage of a brokerage is that you have access to any investments that are offered to the general public. Individual stocks, mutual funds, gold, bitcoin...if you can afford it, you can get it! There may be fees, though, so check thoroughly before you buy.

Step 3: Profit.

What If I Can’t Afford To Contribute?

Can’t afford to invest $10,000 per year? That’s okay, start with what you can. And that’s why I made my spreadsheet available—you can change the 10000 to whatever you want.

If you invest $1000 per year instead of $10,000, this sample three-fund all-world portfolio would still compound to over $640,000 by year 30.

Let it ride for 35 years, and you’ll end up a millionaire.

What’s that? Your 25th birthday is long past? That’s okay, better late than never. If you contribute $1000 a year for 12 years, you’ll still end up with $36,373. That’s a far cry from a million dollars, but it’s certainly better than a closet full of worthless Beanie Babies!

If you say you just can’t afford to start investing, but you make at least $50,000 per year, don’t expect much sympathy from me. I spent four years living on a salary that put me around the poverty line. Once I got my first full-time job, I saved roughly half of a $49,000 salary.

Yet I routinely hear people whine about how hard it is to save money, even when they make well above the national median!

Certainly, some people’s circumstances make that more difficult than others. Some people get terrible health problems early in life. Others are victimized by scams. Divorce is an unfortunately common—and very expensive—occurrence.

But I’m not talking about such issues. I see many people on a daily basis who spend money foolishly. They drive impressive new cars and trucks; they have flashy wardrobes; they wear lots of ostentatious jewelry to show off their ‘wealth.’ Because you couldn’t possibly have money without showing it, right?…

It’s common for people to plan how to spend raises or bonuses before they even hit their bank accounts!

While some writers indulge in excuse-making; I can simply look at my own personal history for proof that it’s possible to save money even on an income that doesn’t even reach $15,000 per year!

Many people just aren’t willing to do what is necessary to make it happen.

Don’t complain—just commit.

Invest whatever you can. Everybody’s situation is different, but it’s wise to start ASAP, even with a small amount. Even $20 a week will help! It’s your future; you’re the only one who can start planning for it.

Nobody else will plan for you, nor will they save on your behalf. If you don’t do it, you’re just hurting your future self.

Which is your prerogative, I guess. But if you choose not to prioritize your future, I don’t want to hear you bellyaching about how difficult it is to live on those meager Social Security checks.

Live on less now, or your future self will be forced to live on less.

Long-term investing really isn’t complicated. Everybody makes it sound complex, but it’s really not. The financial world does have tons of information and jargon, and it’s easy to get confused.

But you really only need the basics. Here they are:

You need surplus money to invest. You don’t need a lot, but more is obviously better.

-

Time is what allows compounding to work so powerfully in your favor.

-

Patience. Don’t react to what you hear on the news. When your friends and co-workers advise you “The market’s dropping! Better get out now before you lose everything,” the best move is to ignore them. Just stay put.

You’re not worried about a week, or a month, or a year from now. You’re worried about a timeframe measured in decades.

The rest of the world can buy today and sell tomorrow—it’s their headache (and tax burden), not yours.

And when you inevitably get scared in the face of a bad economy and a free-falling market…just remember the graphs shown above. That’s your reward for your self-discipline over the years. That’s what has happened for wise investors for generations!

The trials of today lead to the triumphs of tomorrow.

As I’ve noted previously, investing is composed of two parts: math and psychology. The math is pretty simple. The psychology is not.

That’s why you don’t see multimillionaire investors walking around every street corner. Not because the math betrays investors, but because one’s own mind is a difficult thing to master.

Toughen up, though, and history shows that you will prosper beyond belief:

Why Compound Interest Really IS The Eighth Wonder

People frequently claim that Einstein said, “Compound interest is the eighth wonder of the world,” though the phrase actually appears to be the brainchild of an advertising copywriter in the early 1900s.

Regardless of who said it, I think you’ll have to agree by this point: over long periods of time, compound interest really is the 8th wonder of the world!

Put it to work for you.

***

Want to know more about how to invest? Check out my interview with Paul Merriman!

Or you can buy his latest book by clicking on the cover below:

No comments:

Post a Comment